You will need a beautiful fall day, with clear bone-hard skies, a brisk apple-scented wind, and sunset-colored trees shining on the edge of the field. You'll need sunlight illuminating 100 bales of good, thick straw, a bank of sumac the brightest, deepest red you've ever seen, a sturdy pair of farm boots, a strong back, and a pair of weathered hands, ready for plunging into dirt, spreading mulch, and blessing cloves of garlic. You'll need a quarter acre of rich, dark soil, freshly composted with nitrogen-rich manure, and two boxes of golden garlic cloves, the biggest, most beautiful heads saved from last season's harvest. You'll need patience, and some love, enough to gently and efficiently bury each clove into the waiting earth, to walk the field twice over, your back bent, spreading a golden blanket of straw behind you.

You will need a beautiful fall day, with clear bone-hard skies, a brisk apple-scented wind, and sunset-colored trees shining on the edge of the field. You'll need sunlight illuminating 100 bales of good, thick straw, a bank of sumac the brightest, deepest red you've ever seen, a sturdy pair of farm boots, a strong back, and a pair of weathered hands, ready for plunging into dirt, spreading mulch, and blessing cloves of garlic. You'll need a quarter acre of rich, dark soil, freshly composted with nitrogen-rich manure, and two boxes of golden garlic cloves, the biggest, most beautiful heads saved from last season's harvest. You'll need patience, and some love, enough to gently and efficiently bury each clove into the waiting earth, to walk the field twice over, your back bent, spreading a golden blanket of straw behind you.Planting garlic isn't hard. It takes the hard work of your hands and your back, muscles moving and working under the bright sun, the blue sky at your back, the earth heavy and close underneath your knees, dirt under your fingernails. It takes a morning of singing, your song woven together with the song of the high sun and the brisk air, the protective skin on each fat clove, the promise of future bounty.

Plant each clove 6-8 inches apart in two rows with about 10 inches between rows. Bury each clove up to 2 inches deep in the soil. Be careful not to pat down around the clove with your hand; if you do, you will compact the soil, halting circulation and drainage. Row by row, transform the field from a barren piece of soil into a bountiful stand of beautiful garlic. Plant with a friend or you'll get lonely and sweaty. It is important to notice textures and colors, to pay attention to the weight of each clove in your hand, to pause as the wind sweeps over your face, to notice the scent of the soil and the light on the grass.

When all the cloves are safely in their caves of dirt, lay a thick layer of straw over the whole field. Cover the beds and the paths, and make sure it is thick enough to keep out the sunlight and prevent weeds from germinating and chocking out the tender green shoots. By late afternoon, the field will be one shimmering, golden square, the fall sun illuminating the straw and the blue sky framing it, brightening the day. You will be tired, your muscles heavy with use, your arms studded with straw, dust coating your forehead. It is good to be tired.

As the sun dips behind the trees, lie down in the field with the last of the light. Feel the earth beating through the layer of straw. Lying in the field, all you can see is the sky above you, the streaks of light from the setting sun, the occasional dark bird flitting across your line of sight. Think about the life of a plant, emerging from darkness into all this brilliance, and growing up, up, up, always toward the sun. It is a remarkable perspective. Feel the earth touching your head, your neck, the small of your back, your shins, your feet. It is important to lie in the field and bless the garlic. It is a good way to end the day, so close to the dirt, on the same plane as the hundred of cloves you've just put into the ground.

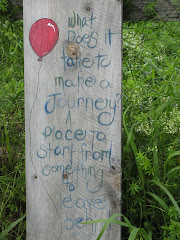

The work of farming is so constant that it is easy to forget that farmers are merely shepherds, and that the true work happens deep under the ground and in the paper-thin green leaves, heedless of our fussing. "Though he works and worries, the farmer never reaches down to where the seed turns into summer. The earth grants." - Rilke.

It is a good practice to lie down in the field and feel the substance of that transformation in our bones.

No comments:

Post a Comment