I came to the pond at the end of a day to say my evening prayers. When I think of prayer I think of the moon, who is always whole but shows herself in pieces. I think of the stillness in the dark water at the center of the pond, of my body moving through that smooth wetness, of the muscle of the water gliding along my skin. When I think of prayer I think of the shape of my skin in the pond, of the precision of each movement of my arm. I swim toward the sun, which is setting over the woods at the edge of Walden. My arms make bubbles that glitter underwater and as I swim a strong line through the middle of the pond, I think: this is what I want to be swimming toward always, the golden track of the sun on this dark, shadowed water on an ordinary day in the fall.

I came to the pond to say my evening prayers. I dive into the water and let it coat me, let my body disappear into the arms of the pond. This is the place I want to write from, speak from, love from. This is what I think of when I think of prayer.

This is fall’s pond, now. The sun is harder as it sets, the water sharper on the skin. The light is sadder, the air scented with endings. Prayers are plentiful here. There is the light on the beach trees and the evergreens, the deepening circle of the sky, my body moving. There is a bird whose name I do not know speaking in the woods. There are shadows on the surface of the pond and smooth stones at its bottom and an endless darkness in its middle where the world around you narrows to the shape of the water and widens to include the breath of every stone and creature you can see.

Geese are flying south and I am swimming toward the sun. Prayers are plentiful here. When I think of prayer I think of details that take my breath away.

This morning I harvested spinach and sorted tomatoes. I separated heads of garlic into cloves that we’ll plant later in the fall. As the afternoon waned to evening I walked down a row of hot peppers, filling my bucket with oranges, reds, yellows, greens. Working in the earth is one way I know how to pray. Swimming to the center of a beloved pond is another. Every work of hands is its own prayer. Every seed, every sunset, every curve of water over skin.

Prayers are plentiful here and words are elusive. What I’m trying to say, with wet hair and dirt-stained hands, is that giving is part of asking, that to truly see a stone or a hawk or a pond is to say its prayer, that prayer is how the earth and I forgive each other. Prayer is the ache in my gut and my muscles after a day spent outside. It is the geese flying south and coming back year after year, buds that overwinter and seeds that produce fruit. Prayer is one of the ways I love this pond. It is the feeling that spreads through your body when you eat a bowl of hot potato soup. It is every simple thing that opens a window of gratitude inside your heart: a ripe tomato, a beloved song, a pond at sunset.

Sunday, September 30, 2007

Recipes

It’s time for a new list of meals for the coming week, so I’ve decided to record everything I ate last week in a new post. I’ll include the recipes here, too, so you can make these yummy things! The trick of it is just throwing whatever looks good into a skillet, listening to good music, and loving the food while it cooks.

Savory Spinach Pie

I’m obsessed with making pies, savory and sweet. I just want to spend all day rolling out flakey, buttery crusts, and fill them with apples and pumpkins and tomatoes.

For the crust:

2 ½ cups whole wheat flour

1 ¼ sticks butter

½ tsp. salt

3-5 Tbs. water.

Combine the salt and flour. Cut in the chilled butter and mix by hand or with a pastry cutter until the dough resembles coarse meal. Gently add the water a little at a time, mixing as you go, just until the dough holds together. If you add too much water the crust will be too hard. Form into a ball, chill, and roll out to fit a 9-inch pie pan. Pre-bake for 20-25 minutes at 350°.

For the filling:

2 red onions, chopped

lots of garlic, minced

2 red peppers, chopped

2-3 bunches spinach, washed and coarsely chopped

3 ears corn, shucked

1 block feta cheese, crumbled

½ cup goat cheese, crumbled

In a medium skillet, cook the onions until soft and translucent. Add the garlic and red peppers and cook a few minute more. When the peppers are tender, add the spinach and cook until the leaves are just wilted. Turn off the heat and stir in the corn, salt and pepper.

Layer the bottom of the pie crust with feta cheese. Spoon half of the filling on top. Crumble the rest of the feta on next, then add the rest of the filling. Cover the top with crumbled goat cheese. Bake at 350° for 30 minutes. Serve hot.

Farm Sandwich

This is what we eat every day for lunch at the farm during high tomato season. Olive oil and balsamic live on the shelves behind the stand. We take turns providing bread and cheese. We never get tired of it.

1 really good tomato – my two favorites are Aunt Ruby’s and Aunt Lillian’s.

a few leaves of fresh, fragrant basil

1 ball fresh mozzarella

olive oil

balsamic

good bread

You know what to do.

Harvest Pasta

This is my classic fall-back dinner during harvest time. I grab whatever looks good from the farm on my way home, throw it in a skillet with a lot of basil, and toss it with pasta, parmesan and olive oil.

This is the combination of stuff I dumped into the skillet last week, but really, any pile of vegetables will be delicious, as long as they’ve been grown with love.

a few onions, red and yellow, sliced thinly

lots of fresh garlic, minced

tomatoes – whatever kinds you like best, chopped

1 bunch of chard or any other green, chopped coarsely

a few red peppers, chopped

1 or 2 zucchini or other summer squash, cubed

lots of basil, chopped

Cook everything in olive oil in a well-oiled skillet in the following order: onions, garlic, red peppers, tomatoes, zucchini, chard, basil. Add some salt and pepper to taste. Toss with hot pasta and lots of parmesan cheese.

Fall Pasta with Bitter Greens and Red Wine Cream Sauce

I had my brother over for dinner and we opened a lovely bottle of red wine. The next day I had about a glass and a half leftover. This is what I did with it.

2 red onions, chopped

garlic, minced

2 apples, minced

2-3 bunches beet greens, washed and chopped

a few leaves fresh sage, chopped

½ cup pine nuts, toasted

½ cup cream

2 Tbs. flour

1 cup red wine

salt and pepper

In a medium skillet, cook the onions until they begin to glow translucent. Add the garlic, apples, and ¼ cup wine, and cook 10-12 minutes more, until the apple are soft and most of the liquid is gone. Add the beet greens, the fresh sage and a bit more wine, cover the pan, and let steam, stirring often, until the greens are tender and the liquid is gone again. Add the pine nuts. Season with salt and pepper. Set aside.

Meanwhile, in small saucepan, heat the remaining wine until just below boiling. Stir in the cream and flour and cook until thick. Add salt to taste.

Toss the hot pasta (I think penne or any of the penne-length curly kinds work best) with the greens, cream sauce, and freshly grated parmesan.

Coming soon: applesauce and pumpkin bread,

Savory Spinach Pie

I’m obsessed with making pies, savory and sweet. I just want to spend all day rolling out flakey, buttery crusts, and fill them with apples and pumpkins and tomatoes.

For the crust:

2 ½ cups whole wheat flour

1 ¼ sticks butter

½ tsp. salt

3-5 Tbs. water.

Combine the salt and flour. Cut in the chilled butter and mix by hand or with a pastry cutter until the dough resembles coarse meal. Gently add the water a little at a time, mixing as you go, just until the dough holds together. If you add too much water the crust will be too hard. Form into a ball, chill, and roll out to fit a 9-inch pie pan. Pre-bake for 20-25 minutes at 350°.

For the filling:

2 red onions, chopped

lots of garlic, minced

2 red peppers, chopped

2-3 bunches spinach, washed and coarsely chopped

3 ears corn, shucked

1 block feta cheese, crumbled

½ cup goat cheese, crumbled

In a medium skillet, cook the onions until soft and translucent. Add the garlic and red peppers and cook a few minute more. When the peppers are tender, add the spinach and cook until the leaves are just wilted. Turn off the heat and stir in the corn, salt and pepper.

Layer the bottom of the pie crust with feta cheese. Spoon half of the filling on top. Crumble the rest of the feta on next, then add the rest of the filling. Cover the top with crumbled goat cheese. Bake at 350° for 30 minutes. Serve hot.

Farm Sandwich

This is what we eat every day for lunch at the farm during high tomato season. Olive oil and balsamic live on the shelves behind the stand. We take turns providing bread and cheese. We never get tired of it.

1 really good tomato – my two favorites are Aunt Ruby’s and Aunt Lillian’s.

a few leaves of fresh, fragrant basil

1 ball fresh mozzarella

olive oil

balsamic

good bread

You know what to do.

Harvest Pasta

This is my classic fall-back dinner during harvest time. I grab whatever looks good from the farm on my way home, throw it in a skillet with a lot of basil, and toss it with pasta, parmesan and olive oil.

This is the combination of stuff I dumped into the skillet last week, but really, any pile of vegetables will be delicious, as long as they’ve been grown with love.

a few onions, red and yellow, sliced thinly

lots of fresh garlic, minced

tomatoes – whatever kinds you like best, chopped

1 bunch of chard or any other green, chopped coarsely

a few red peppers, chopped

1 or 2 zucchini or other summer squash, cubed

lots of basil, chopped

Cook everything in olive oil in a well-oiled skillet in the following order: onions, garlic, red peppers, tomatoes, zucchini, chard, basil. Add some salt and pepper to taste. Toss with hot pasta and lots of parmesan cheese.

Fall Pasta with Bitter Greens and Red Wine Cream Sauce

I had my brother over for dinner and we opened a lovely bottle of red wine. The next day I had about a glass and a half leftover. This is what I did with it.

2 red onions, chopped

garlic, minced

2 apples, minced

2-3 bunches beet greens, washed and chopped

a few leaves fresh sage, chopped

½ cup pine nuts, toasted

½ cup cream

2 Tbs. flour

1 cup red wine

salt and pepper

In a medium skillet, cook the onions until they begin to glow translucent. Add the garlic, apples, and ¼ cup wine, and cook 10-12 minutes more, until the apple are soft and most of the liquid is gone. Add the beet greens, the fresh sage and a bit more wine, cover the pan, and let steam, stirring often, until the greens are tender and the liquid is gone again. Add the pine nuts. Season with salt and pepper. Set aside.

Meanwhile, in small saucepan, heat the remaining wine until just below boiling. Stir in the cream and flour and cook until thick. Add salt to taste.

Toss the hot pasta (I think penne or any of the penne-length curly kinds work best) with the greens, cream sauce, and freshly grated parmesan.

Coming soon: applesauce and pumpkin bread,

Friday, September 28, 2007

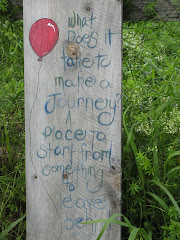

How to Love a Place

This is a rather long essay which I originally wrote for my application to Sterling. It also feels to me like my current credo. Everything I believe in right now is written here. It seems fitting to post it, since everything I write these days seems to be, in one way or another, about what it means to love a place.

How to Love a Place

1. “I am my beloved’s and my beloved is mine.”

I am walking home from the Power Ridge, an outcropping of glacial granite and glittery quartz in the woods of Grafton County, New Hampshire. It is four o’clock, and already the sun is setting, a pink and golden slash on the western horizon. The only sound is the soft fall of my snowshoes as they slide through the snow, and the evening whispering of the naked trees. I am walking slowly, pacing myself to the rhythm of the sinking sun as it spreads its golden across the sharp world of winter whites and grays and blues.

We discovered the Power Ridge by accident, its rocky back unearthed due to some logging on the land adjacent to ours. Unable to resist the call of open spaces, we followed the logging cut one year until we stumbled across this ridge. “There’s something scared about this place,” my mother said. She named it the Power Ridge and the name stuck, though it is not marked on any official map. It is not especially high or dramatic – just a granite ledge with a few spruces growing along its edges. In the winter it boasts a sweeping view of Mt. Cardigan, but in the summer the path through the logging cut is overrun with wild blackberries, and the view obstructed by the racket of green. But it is one of those rare places that, once you’ve been there, never lets you go. Standing on the ridge, I get a sense of endless space, as if the thousands of years that have shaped these woods are very close, listening and watching. On a cold afternoon in December, looking out across the forest toward white-tipped Cardigan, I feel as if I am standing in the very heart, the very essence of winter. Here the wind and the silence are king, and each time I make the journey through the snowy woods toward the sky, I am refreshed and renewed.

Walking home along the familiar trail, at that scared hour on the edge of dusk, when the day and the night meet and bow to each other in a beautiful dance and all the trees bend close together in prayer, I am suddenly overcome with the weight of how much I love this place. My grandparents’ bought this parcel of hilly woodlands in the fifties, when land was cheap and abundant. I grew up catching newts in its streams and rambling on secret paths among its pine and maple. But what does it mean to own a place? If I have any right to these woods, it is not because of any paper that my parents have tucked away in a drawer. Ownership is more complex and sacred than any deed or human law. If I own these woods, it is only because they, too, own me. If these trees and this ridgeline and this snowy path belong to me, it is only because I, too, belong to them. “I am my beloved’s and my beloved is mine,” writes the poet of the Song of Songs. Love, it turns out, is the only ownership, love and wonder and hard work.

I am almost home, and I pause at the edge of a meadow to look back at the trail through the woods from which I’ve come. The sun has disappeared behind the bulk of Braley Hill and the sky is hardening into a cold winter blue. The distant ridges are outlined in shadow. As darkness settles over the meadow, with the mountains as my witness, I make a pact to own this land and in return, to be owned by it.

2. Falling In Wonder

I love winter. I love the slow decent into darkness as the days quicken and the nights lengthen. I love it when bone-hard Orion first rises over the November hills. I love the cold mornings that shock me awake, the harsh colors and sharp contrasts of the landscape, and the white emptiness of the forest. So each year, in late April, when the ground begins to thaw, and the woods are fragrant with mud, I am always astounded at my own happiness. I am surprised, again and again, by my own reaction to the return of the light and the budding earth. Spring awakes a quickness in me. It sets me singing with possibility. It is impossible to walk among cascades of cherry blossoms and patches of daffodils without sensing something of their easy joy and hard-earned playfulness. Spring opens in my heart a renewed wonder, a wonder that, though it happens each season, grows and grows, like the new buds that open daily into leaf.

Spring is the unexpected season. Everywhere, the voices of the young green shoots cry out about survival. After the long, cold winter, the world emerges triumphant. Buds that have been waiting since September, shaken and broken by blizzards, erupt proudly into new life. The hard earth softens and opens to receive seed after seed. Colors once again throw their finery over the landscape – the sweet red of young sugar maples, the shy pink of the dogwoods, wildflowers bursting purple and blue across the fields. Everywhere the woods are a raucous of greenery. The mere fact of these things, of colors and sunshine, of the ability of oak and lily and cattail to survive and blossom, is enough to stop me mid-step in wonder. We take so much for granted in this world: the land and its resources, and even the cycles of loss and renewal that are the basis of all life. Spring reminds me that there is no miracle too small, that every bud that opens is a testament to the unbelievable tenacity of the earth. Everywhere I go, I am stunned with wonder. It is my breath and my speech, and even in sleep, it doesn’t leave me.

Four hundred feet below the Power Ridge, in a small glade of spruce and beech, I am sitting at the edge of a small, mossy bog. It is early evening, and the air is loud with peppers. I am sheltered by a lacy canopy of young leaves, bright and delicate as feathers. The first lady slippers and trilliums are blooming, and the bog is teeming with life after its icy sleep. Frogs and salamanders are waking up and the forest is heavy with a sense of excitement. Leaning against an old oak, watching the patterns the wind makes on the water, I am falling in wonder. It is not like falling in love. I have loved this place my whole life and I know what it feels like. Falling in wonder is different. It is the realization that though I am merely a shadow in the life of this bog, I want it to last, beyond me and beyond my children. Wonder has its own scent: freshly cut hay and rich, dark soil, a clean wind blowing through the budding trees. It is something palpable, something I can hold in my hands. It is the desire to be a part of something bigger than myself, the knowledge that without the land, in all its specifics, I am nothing.

3. Hot Sun and Hard Work

It is early morning, and though it is August, it is still cool. A thin silver mist is rising off the fields, the moon is setting on the western horizon, and I am kneeling in the dirt, harvesting carrots. There are four beds of them, their feathery green tops stretching out in a lush carpet to either side of me. I feel small and clunky when I am out in these fields, among the simple elegance of vegetables.

Summer is the season of hands. It is the season of planting and hoeing, weeding and pruning and harvesting. In the summer I rise at dawn and come to these fields, where, all day, I tend to the earth. I move slowly among rows of turnips and beets, meticulously searching out the young pursline and pigsweed among them. I walk the fields just after dawn, harvesting spinach and arugula in the quiet morning before the full heat of the day settles over the farm. In the summer my body adjusts to the rhythms of the land. A permanent layer of dirt settles under my fingernails. My hands grow calluses in the places where the hoe touches my skin. My world narrows and widens to the cycles of the land: the smell just before a rain, the lengthening days, the heat and the sunshine, the wind, and always, the knowledge of the first frost that will, inevitably, come.

Farming is hard, rhythmic work, and each year, it is more of the same. The tomatoes have to be staked and tied, the cukes have to be harvested every other day, the late planting of lettuce has to go in, the summer raspberries have to be pruned, the kale has to be weeded, the strawberries have to be mulched. The earth is not forgiving, but it does yield to hard work and tender care. Each season the pumpkins grow from two-centimeter-high seedlings into a knee-high forest of thick green vines. The tomatoes ripen into shades of red-orange and bright yellow, deep purple and blushing rose. I spend long mornings snapping silver-green leaves of kale from tough stalks and cutting fragile heads of lettuce from the ground. These are no small miracles. I started farming four years ago and it has revolutionized my life. I have never been as close to the earth as I am each summer, as I guide crop after crop through its life toward fruition.

At the heart of farming is the desire to be a part of the process of growing things. I do not farm to dominate and destroy, or to make a profit. I farm because, above all, I love the earth, and I am always tying to get closer to its heart. I want to understand its vital cycles, its power and its vulnerability, what it can give and what it can take away. The earth is a tough and compassionate teacher. All summer, as I hoe the beds and irrigate the fields, I am riding out a prayer. I put everything of myself into the hard work of my hands, but in the end, it is the earth that produces the bounty. Farming is a partnership, an ownership, between me and the land I love. As a farmer I am a witness and a guide, a student and a teacher, and, more than anything, a friend.

I love wild places. But this morning, pausing in my work to watch the last bony ridge of the moon fade behind the trees, I am thinking of the miracle of cultivated land and the beauty of carrots. The thin orange root I am holding in my hand, rough and covered in dirt, with its crown of greenery, is the fulfillment of a promise. It is not merely a vegetable – it is hours of sun and rain and the work of hands. I am blessed to have been a part of this process, a process that begins with loving the growing things of the earth. I wipe the carrot on my jeans and take a bite. The sweet, field-fresh flavor is heightened with the acrid taste of dirt. It is, of course, the best carrot I have ever eaten.

4. Shehecheyanu

Barukh attah Adonai eloheinu melekh ha-olam, she-hecheyanu v’ki-yemanu v’higianu lazeman hazeh. Blessed art thou, Lord our God, Master of the Universe, who has kept us alive and sustained us and enabled us to reach this season.

Shehecheyanu is my favorite Jewish prayer. It is traditionally recited on the first night of a holiday, or on the occasion of anything new or unusual: the birth of a baby, the beginning of school, the start of a new job, a wedding or Bar-mitzvah. It is a prayer of gratitude to remind us how lucky we are to arrive each season at a moment of celebration. At its root is the idea that to simply arrive, whole and healthy, in each new day of our lives, is a miracle and a blessing.

Autumn is the season of arrival. After the messy abundance of summer and before the long sleep of winter, fall is the harvest season, the season of gathering and reaping. The ground hardens and freezes, the leaves turn golden and fall, the crops fold back into the earth. There is something sweet and sad in the evening air, something that stills me and steadies me. It is the season of slowing down and starting over, the beginning of the cycle of death and rebirth that guides the land through the winter and back into spring. In the fall, it is the knowledge of being present in that ancient, sacred cycle, that sustains me and carries me forward.

Shehecheyanu is a prayer about the miracle of being sustained, alive, through each moment. I believe that every day merits a Shehecheyanu. Every moment we are alive is worth celebrating. Though it is traditionally only said on special occasions, I say Shehecheyanu nearly every day. I say is as a blessing over my food. I say it as I am preparing the garden for winter and storing away the last of the beets in the cellar. Walking through the autumn woods, I say it to the falling leaves and to the last blue waters of the ponds before they ice over into black. I do not believe in God, but I do believe in the miracle of reaching, again and again, another season. I do believe in the miracle of being sustained, moment by moment, into the next day, the next month, the next season. Arrival is more complicated than simply waking up each morning. Arrival means coming from somewhere. Lives, like seasons, do not exist in vacuums. Fall comes from summer, and from fall comes winter. To arrive is to be aware of the delicate and beautiful dance of the earth, and to say a Shehecheyanu for that dance.

I am back in the woods of Grafton County, walking up to the Power Ridge through the golden maze of beach and oak. The woods are heavy with the sharp scent of wholeness and fulfillment. When I reach the top, I will say a prayer for arrival, a prayer for the woods and the streams and the gardens that have sustained me and kept me alive and allowed me to reach this moment on this beloved ridge. With the wind in my face, looking out from this season into the next, I will open my arms to the sky, and bow down to the earth, and sing a Shehecheyanu for the land.

5. How to Love a Place

If there are solutions to the environmental crises of our time, they lie in our willingness to enter into a new kind of ownership with the earth, an ownership rooted in reverence, an ownership defined not by rending and wasting, by power-over and use-of, but by keen understanding and honest love and mutual responsibility. They lie in our capacity to fall in wonder, walking daily from miracle to miracle, our capacity to steep ourselves so completely in the beauty and the bounty of the natural world that to destroy it becomes impossible. They lie in our ability to be tender shepards of the land, to kneel down in the earth and plunge our hands into the dirt.

If there are solutions to the environmental crises of our day, they lie in the capacity of each of us to arrive, moment by moment, in the season of gratitude and grace. They lie in our capacity to guide and sustain not only ourselves, but our fields and our mountains and our woodlands, toward a season in which our footsteps fall in harmony with those of the fox and black bear and the cardinal. Now is the time for concrete change, but it must begin in the specifics of how we love a place: the way the October sunlight falls on a pumpkin vine, the sharp curve of a distant ridge, whitened and sharpened by winter, the ordinary song of a chickadee in the garden, the familiar sensation of the rough and weathered bark of a sugar maple against the palm of your hand.

How to Love a Place

1. “I am my beloved’s and my beloved is mine.”

I am walking home from the Power Ridge, an outcropping of glacial granite and glittery quartz in the woods of Grafton County, New Hampshire. It is four o’clock, and already the sun is setting, a pink and golden slash on the western horizon. The only sound is the soft fall of my snowshoes as they slide through the snow, and the evening whispering of the naked trees. I am walking slowly, pacing myself to the rhythm of the sinking sun as it spreads its golden across the sharp world of winter whites and grays and blues.

We discovered the Power Ridge by accident, its rocky back unearthed due to some logging on the land adjacent to ours. Unable to resist the call of open spaces, we followed the logging cut one year until we stumbled across this ridge. “There’s something scared about this place,” my mother said. She named it the Power Ridge and the name stuck, though it is not marked on any official map. It is not especially high or dramatic – just a granite ledge with a few spruces growing along its edges. In the winter it boasts a sweeping view of Mt. Cardigan, but in the summer the path through the logging cut is overrun with wild blackberries, and the view obstructed by the racket of green. But it is one of those rare places that, once you’ve been there, never lets you go. Standing on the ridge, I get a sense of endless space, as if the thousands of years that have shaped these woods are very close, listening and watching. On a cold afternoon in December, looking out across the forest toward white-tipped Cardigan, I feel as if I am standing in the very heart, the very essence of winter. Here the wind and the silence are king, and each time I make the journey through the snowy woods toward the sky, I am refreshed and renewed.

Walking home along the familiar trail, at that scared hour on the edge of dusk, when the day and the night meet and bow to each other in a beautiful dance and all the trees bend close together in prayer, I am suddenly overcome with the weight of how much I love this place. My grandparents’ bought this parcel of hilly woodlands in the fifties, when land was cheap and abundant. I grew up catching newts in its streams and rambling on secret paths among its pine and maple. But what does it mean to own a place? If I have any right to these woods, it is not because of any paper that my parents have tucked away in a drawer. Ownership is more complex and sacred than any deed or human law. If I own these woods, it is only because they, too, own me. If these trees and this ridgeline and this snowy path belong to me, it is only because I, too, belong to them. “I am my beloved’s and my beloved is mine,” writes the poet of the Song of Songs. Love, it turns out, is the only ownership, love and wonder and hard work.

I am almost home, and I pause at the edge of a meadow to look back at the trail through the woods from which I’ve come. The sun has disappeared behind the bulk of Braley Hill and the sky is hardening into a cold winter blue. The distant ridges are outlined in shadow. As darkness settles over the meadow, with the mountains as my witness, I make a pact to own this land and in return, to be owned by it.

2. Falling In Wonder

I love winter. I love the slow decent into darkness as the days quicken and the nights lengthen. I love it when bone-hard Orion first rises over the November hills. I love the cold mornings that shock me awake, the harsh colors and sharp contrasts of the landscape, and the white emptiness of the forest. So each year, in late April, when the ground begins to thaw, and the woods are fragrant with mud, I am always astounded at my own happiness. I am surprised, again and again, by my own reaction to the return of the light and the budding earth. Spring awakes a quickness in me. It sets me singing with possibility. It is impossible to walk among cascades of cherry blossoms and patches of daffodils without sensing something of their easy joy and hard-earned playfulness. Spring opens in my heart a renewed wonder, a wonder that, though it happens each season, grows and grows, like the new buds that open daily into leaf.

Spring is the unexpected season. Everywhere, the voices of the young green shoots cry out about survival. After the long, cold winter, the world emerges triumphant. Buds that have been waiting since September, shaken and broken by blizzards, erupt proudly into new life. The hard earth softens and opens to receive seed after seed. Colors once again throw their finery over the landscape – the sweet red of young sugar maples, the shy pink of the dogwoods, wildflowers bursting purple and blue across the fields. Everywhere the woods are a raucous of greenery. The mere fact of these things, of colors and sunshine, of the ability of oak and lily and cattail to survive and blossom, is enough to stop me mid-step in wonder. We take so much for granted in this world: the land and its resources, and even the cycles of loss and renewal that are the basis of all life. Spring reminds me that there is no miracle too small, that every bud that opens is a testament to the unbelievable tenacity of the earth. Everywhere I go, I am stunned with wonder. It is my breath and my speech, and even in sleep, it doesn’t leave me.

Four hundred feet below the Power Ridge, in a small glade of spruce and beech, I am sitting at the edge of a small, mossy bog. It is early evening, and the air is loud with peppers. I am sheltered by a lacy canopy of young leaves, bright and delicate as feathers. The first lady slippers and trilliums are blooming, and the bog is teeming with life after its icy sleep. Frogs and salamanders are waking up and the forest is heavy with a sense of excitement. Leaning against an old oak, watching the patterns the wind makes on the water, I am falling in wonder. It is not like falling in love. I have loved this place my whole life and I know what it feels like. Falling in wonder is different. It is the realization that though I am merely a shadow in the life of this bog, I want it to last, beyond me and beyond my children. Wonder has its own scent: freshly cut hay and rich, dark soil, a clean wind blowing through the budding trees. It is something palpable, something I can hold in my hands. It is the desire to be a part of something bigger than myself, the knowledge that without the land, in all its specifics, I am nothing.

3. Hot Sun and Hard Work

It is early morning, and though it is August, it is still cool. A thin silver mist is rising off the fields, the moon is setting on the western horizon, and I am kneeling in the dirt, harvesting carrots. There are four beds of them, their feathery green tops stretching out in a lush carpet to either side of me. I feel small and clunky when I am out in these fields, among the simple elegance of vegetables.

Summer is the season of hands. It is the season of planting and hoeing, weeding and pruning and harvesting. In the summer I rise at dawn and come to these fields, where, all day, I tend to the earth. I move slowly among rows of turnips and beets, meticulously searching out the young pursline and pigsweed among them. I walk the fields just after dawn, harvesting spinach and arugula in the quiet morning before the full heat of the day settles over the farm. In the summer my body adjusts to the rhythms of the land. A permanent layer of dirt settles under my fingernails. My hands grow calluses in the places where the hoe touches my skin. My world narrows and widens to the cycles of the land: the smell just before a rain, the lengthening days, the heat and the sunshine, the wind, and always, the knowledge of the first frost that will, inevitably, come.

Farming is hard, rhythmic work, and each year, it is more of the same. The tomatoes have to be staked and tied, the cukes have to be harvested every other day, the late planting of lettuce has to go in, the summer raspberries have to be pruned, the kale has to be weeded, the strawberries have to be mulched. The earth is not forgiving, but it does yield to hard work and tender care. Each season the pumpkins grow from two-centimeter-high seedlings into a knee-high forest of thick green vines. The tomatoes ripen into shades of red-orange and bright yellow, deep purple and blushing rose. I spend long mornings snapping silver-green leaves of kale from tough stalks and cutting fragile heads of lettuce from the ground. These are no small miracles. I started farming four years ago and it has revolutionized my life. I have never been as close to the earth as I am each summer, as I guide crop after crop through its life toward fruition.

At the heart of farming is the desire to be a part of the process of growing things. I do not farm to dominate and destroy, or to make a profit. I farm because, above all, I love the earth, and I am always tying to get closer to its heart. I want to understand its vital cycles, its power and its vulnerability, what it can give and what it can take away. The earth is a tough and compassionate teacher. All summer, as I hoe the beds and irrigate the fields, I am riding out a prayer. I put everything of myself into the hard work of my hands, but in the end, it is the earth that produces the bounty. Farming is a partnership, an ownership, between me and the land I love. As a farmer I am a witness and a guide, a student and a teacher, and, more than anything, a friend.

I love wild places. But this morning, pausing in my work to watch the last bony ridge of the moon fade behind the trees, I am thinking of the miracle of cultivated land and the beauty of carrots. The thin orange root I am holding in my hand, rough and covered in dirt, with its crown of greenery, is the fulfillment of a promise. It is not merely a vegetable – it is hours of sun and rain and the work of hands. I am blessed to have been a part of this process, a process that begins with loving the growing things of the earth. I wipe the carrot on my jeans and take a bite. The sweet, field-fresh flavor is heightened with the acrid taste of dirt. It is, of course, the best carrot I have ever eaten.

4. Shehecheyanu

Barukh attah Adonai eloheinu melekh ha-olam, she-hecheyanu v’ki-yemanu v’higianu lazeman hazeh. Blessed art thou, Lord our God, Master of the Universe, who has kept us alive and sustained us and enabled us to reach this season.

Shehecheyanu is my favorite Jewish prayer. It is traditionally recited on the first night of a holiday, or on the occasion of anything new or unusual: the birth of a baby, the beginning of school, the start of a new job, a wedding or Bar-mitzvah. It is a prayer of gratitude to remind us how lucky we are to arrive each season at a moment of celebration. At its root is the idea that to simply arrive, whole and healthy, in each new day of our lives, is a miracle and a blessing.

Autumn is the season of arrival. After the messy abundance of summer and before the long sleep of winter, fall is the harvest season, the season of gathering and reaping. The ground hardens and freezes, the leaves turn golden and fall, the crops fold back into the earth. There is something sweet and sad in the evening air, something that stills me and steadies me. It is the season of slowing down and starting over, the beginning of the cycle of death and rebirth that guides the land through the winter and back into spring. In the fall, it is the knowledge of being present in that ancient, sacred cycle, that sustains me and carries me forward.

Shehecheyanu is a prayer about the miracle of being sustained, alive, through each moment. I believe that every day merits a Shehecheyanu. Every moment we are alive is worth celebrating. Though it is traditionally only said on special occasions, I say Shehecheyanu nearly every day. I say is as a blessing over my food. I say it as I am preparing the garden for winter and storing away the last of the beets in the cellar. Walking through the autumn woods, I say it to the falling leaves and to the last blue waters of the ponds before they ice over into black. I do not believe in God, but I do believe in the miracle of reaching, again and again, another season. I do believe in the miracle of being sustained, moment by moment, into the next day, the next month, the next season. Arrival is more complicated than simply waking up each morning. Arrival means coming from somewhere. Lives, like seasons, do not exist in vacuums. Fall comes from summer, and from fall comes winter. To arrive is to be aware of the delicate and beautiful dance of the earth, and to say a Shehecheyanu for that dance.

I am back in the woods of Grafton County, walking up to the Power Ridge through the golden maze of beach and oak. The woods are heavy with the sharp scent of wholeness and fulfillment. When I reach the top, I will say a prayer for arrival, a prayer for the woods and the streams and the gardens that have sustained me and kept me alive and allowed me to reach this moment on this beloved ridge. With the wind in my face, looking out from this season into the next, I will open my arms to the sky, and bow down to the earth, and sing a Shehecheyanu for the land.

5. How to Love a Place

If there are solutions to the environmental crises of our time, they lie in our willingness to enter into a new kind of ownership with the earth, an ownership rooted in reverence, an ownership defined not by rending and wasting, by power-over and use-of, but by keen understanding and honest love and mutual responsibility. They lie in our capacity to fall in wonder, walking daily from miracle to miracle, our capacity to steep ourselves so completely in the beauty and the bounty of the natural world that to destroy it becomes impossible. They lie in our ability to be tender shepards of the land, to kneel down in the earth and plunge our hands into the dirt.

If there are solutions to the environmental crises of our day, they lie in the capacity of each of us to arrive, moment by moment, in the season of gratitude and grace. They lie in our capacity to guide and sustain not only ourselves, but our fields and our mountains and our woodlands, toward a season in which our footsteps fall in harmony with those of the fox and black bear and the cardinal. Now is the time for concrete change, but it must begin in the specifics of how we love a place: the way the October sunlight falls on a pumpkin vine, the sharp curve of a distant ridge, whitened and sharpened by winter, the ordinary song of a chickadee in the garden, the familiar sensation of the rough and weathered bark of a sugar maple against the palm of your hand.

Hoarding Season

It is hoarding season. It comes with the longer nights and the chilly mornings and the leaves that turn red and brown and orange and fall from the branches. It comes with the first early frost, with the squash harvest and the harder sunsets in the west. My house is slowly filling up with the good, hard food that will keep me going in the winter: potatoes, pie pumpkins, winter squash, onions. It is hard to go a whole season without green things. In this age of planes and computers we are used to getting whatever we want whenever we want it. I am not immune to this. In the darkest months I crave fresh lettuce, red peppers and blueberries. I don’t go six months without eating anything green. But there is something important about the need to prepare for a season. There is something important in the act of storing away food and strength for the times we’ll need them most. There is something that happens to the body, a reaction to the cold and the darkness, a need to keep things close. Maybe it is just basic human instinct, like the instinct to keep warm and to eat and to be with other people.

It is hoarding season. Winter food is different from summer food. In the cold months I crave thick potato soup, fried onions, roasted squash and pumpkin seeds, leeks simmered a long time in fragrant broth. Food is our most basic need, and whether we notice it or not, it links us directly to the soil, the rain, the sunlight. It is hoarding season. This week in a friend’s bright kitchen on the edge of the woods, I jarred ten quarts of applesauce. It was a clear cool night one day before the full moon. I peeled apples while Jo chopped tomatoes. We set two big pots on the stove, side by side, and the smells of harvest filled the kitchen and spilled out into the night. Apples, honey, cinnamon, cloves, tomatoes, basil, parsley, garlic. We watched and talked as the apples bubbled and fell apart into a golden fragrance and the red tomatoes thickened as they cooked.

It is hoarding season. I want to gather all the good food we grow close to me and not let it out of my sight. This is a gut reaction. My body tells me what I need, and it is speaking now of thick soups that simmer all day on the stove and will keep me warm for a long time after I eat them. This is a need that is older than me, a need that has been around as long as humans have been making homes. We are not as disconnected from the land as our supermarkets and our televisions lead us to believe. It is not a crime to buy lettuce and red peppers in December, but preparing for the winter is no small feat. Food sustains something in us that is deeper than muscle and blood. It sustains our homes, our families, our loves, our friendships. We are fragile in the winter. The world tightens and hardens. It takes a lot of energy to keep warm. We need food that will keep us warm, that will keep a core of sunlight deep in our chests.

It is hoarding season. The harvest is in. All our winter squash is boxed and cured. I spend the mornings at the farm stand popping garlic for seed and cleaning onions. Our tomatoes are still thriving, but an early frost killed our summer squash. It is time to pause, to take a breath and take stock of where we are, to prepare for the long darkness. Hoarding used to be a tool for survival. If you didn’t have enough salted meat and cornmeal and flour and apples, you would starve. It used to be that preparing for winter was more than getting out your wool sweaters and putting away your t-shirts. Strawberries are a blessing, as is fresh corn and tomatoes and an abundance of zucchini. But we do not live in a world that can produce these things endlessly without consequence. It is also a blessing that seasons end and are renewed with others, that we live in a world rich and varied enough that each season brings its own joy.

It is hoarding season, and I am preparing for winter. I take long walks and let the sunlight filter into my blood. I spend the evenings freezing corn and canning tomatoes. This is one of the ways I make peace with the darkness. There is more than tomatoes and basil and garlic in every glass jar of tomato sauce I put into in my pantry. In every jar there is the sum total of a season’s hard work. In every jar there are the hours spent weeding and mulching and tying tomatoes. In every jar is the weight of a red fruit in my hand and the light that touched them as we harvested in the late afternoon. These are things that will feed me over the winter. The hard work, the sunshine, the memory of laughter and aching muscles, the rare taste of rain, the blessing of ripe fruit, the celebration of the harvest, that we’ve made it through another season. Food is sustenance, and sustenance is not free.

Earlier this week a young girl came to the farm with her mother to pick out a pumpkin. She was curious about everything, and asked me what I was doing as I separated heads of garlic into cloves for planting. I explained to her that each clove of garlic would grow into a new plant next summer. She watched me for a while and then went back to the serious task of choosing a pumpkin. Later, as she helped her mom pick out vegetables and bring them to the counter, she asked me: “Why do you grow things?” I was taken by surprise. “Everything you see in the supermarket comes from a farm,” I told her. “Somebody has to grow it.” A simplified and watered-down answer to a very important and rarely-asked question.

Everything that eats must also kill. I am just beginning to realize how important it is not to separate myself from this process, this cycle of killing and growing and eating. We grow things so that we can hoard them. We grow things because we love the earth, because our hands crave dirt, because we need to eat. This is the most basic, the simplest truth. We have to eat to stay alive. There is no way around this, no easier way to explain it. Things that live want to keep living. I grow food because I am attached to my life on this planet. We need to eat, and in order to do that, we kill a lot of things. We grow broccoli and corn and cucumbers, but we kill a lot of other plants, plants with names of their own: pigweed, purslane, ragweed, mustard root, dandelion, bindweed, sedge grass. We kill a lot of bugs – potato beetles, bean beetles, horn worms, aphids. Everything that eats must also kill. You can spray a field of potatoes with poison to kill all the potato beetles. Or you can spend hours in the hot sun moving down the row by hand, examining the leaves for beetles and squishing every one you see. This is a large part of our work in July: killing potato bug larva one by one, before they can perform the most basic act of survival and make more of themselves. In exchange for the life of a potato beetle we get a hard brown potato. A meal. I don’t know if this is a fair trade, but it is a trade I’m willing to make. I’m walking down those rows squishing those bugs by hand because the alternative is a lot of needless death.

There are complexities upon complexities in farming. I didn’t know how to answer that young girl’s question and I still don’t. All I have to offer her are the truths I know and refuse to ignore, the few hard facts that do not change, that shape our relationship to the land. Everything that eats must also kill. Everything that lives only wants to keep living, only wants to be remembered. We need to eat. We need to eat.

It is the end of September, and it is hoarding season. I am storing away onions and kabocha squash, and making of my kitchen an offering: applesauce, tomato sauce, thick garlic broth, raspberry jam, pumpkin butter, pickled beets, salsa. The nights are getting colder and my kitchen is gathering steam. It is not enough to fill our pantries with glass jars that remind us of our need for the land and what it will give us if we are patient and careful. It is not enough, but it is a start. My body knows what it needs. It is the season of yellow onions and butternut squash. I am filling my house with the scents of things that come from the earth: sweet basil and sharp garlic, roasted pumpkin, baked apples, honey. Winter is coming and this is the only thing I know how to do. I am filling my house with this good, solid food, this food that has the hard work of hands stitched into its flesh, this food that carries in its seeds both life and death, this food that is sustence and sunlight, that is patience and reverence, this food that binds us to the earth and blesses us and sustains us, this food that is our one undeniable prayer.

It is hoarding season. Winter food is different from summer food. In the cold months I crave thick potato soup, fried onions, roasted squash and pumpkin seeds, leeks simmered a long time in fragrant broth. Food is our most basic need, and whether we notice it or not, it links us directly to the soil, the rain, the sunlight. It is hoarding season. This week in a friend’s bright kitchen on the edge of the woods, I jarred ten quarts of applesauce. It was a clear cool night one day before the full moon. I peeled apples while Jo chopped tomatoes. We set two big pots on the stove, side by side, and the smells of harvest filled the kitchen and spilled out into the night. Apples, honey, cinnamon, cloves, tomatoes, basil, parsley, garlic. We watched and talked as the apples bubbled and fell apart into a golden fragrance and the red tomatoes thickened as they cooked.

It is hoarding season. I want to gather all the good food we grow close to me and not let it out of my sight. This is a gut reaction. My body tells me what I need, and it is speaking now of thick soups that simmer all day on the stove and will keep me warm for a long time after I eat them. This is a need that is older than me, a need that has been around as long as humans have been making homes. We are not as disconnected from the land as our supermarkets and our televisions lead us to believe. It is not a crime to buy lettuce and red peppers in December, but preparing for the winter is no small feat. Food sustains something in us that is deeper than muscle and blood. It sustains our homes, our families, our loves, our friendships. We are fragile in the winter. The world tightens and hardens. It takes a lot of energy to keep warm. We need food that will keep us warm, that will keep a core of sunlight deep in our chests.

It is hoarding season. The harvest is in. All our winter squash is boxed and cured. I spend the mornings at the farm stand popping garlic for seed and cleaning onions. Our tomatoes are still thriving, but an early frost killed our summer squash. It is time to pause, to take a breath and take stock of where we are, to prepare for the long darkness. Hoarding used to be a tool for survival. If you didn’t have enough salted meat and cornmeal and flour and apples, you would starve. It used to be that preparing for winter was more than getting out your wool sweaters and putting away your t-shirts. Strawberries are a blessing, as is fresh corn and tomatoes and an abundance of zucchini. But we do not live in a world that can produce these things endlessly without consequence. It is also a blessing that seasons end and are renewed with others, that we live in a world rich and varied enough that each season brings its own joy.

It is hoarding season, and I am preparing for winter. I take long walks and let the sunlight filter into my blood. I spend the evenings freezing corn and canning tomatoes. This is one of the ways I make peace with the darkness. There is more than tomatoes and basil and garlic in every glass jar of tomato sauce I put into in my pantry. In every jar there is the sum total of a season’s hard work. In every jar there are the hours spent weeding and mulching and tying tomatoes. In every jar is the weight of a red fruit in my hand and the light that touched them as we harvested in the late afternoon. These are things that will feed me over the winter. The hard work, the sunshine, the memory of laughter and aching muscles, the rare taste of rain, the blessing of ripe fruit, the celebration of the harvest, that we’ve made it through another season. Food is sustenance, and sustenance is not free.

Earlier this week a young girl came to the farm with her mother to pick out a pumpkin. She was curious about everything, and asked me what I was doing as I separated heads of garlic into cloves for planting. I explained to her that each clove of garlic would grow into a new plant next summer. She watched me for a while and then went back to the serious task of choosing a pumpkin. Later, as she helped her mom pick out vegetables and bring them to the counter, she asked me: “Why do you grow things?” I was taken by surprise. “Everything you see in the supermarket comes from a farm,” I told her. “Somebody has to grow it.” A simplified and watered-down answer to a very important and rarely-asked question.

Everything that eats must also kill. I am just beginning to realize how important it is not to separate myself from this process, this cycle of killing and growing and eating. We grow things so that we can hoard them. We grow things because we love the earth, because our hands crave dirt, because we need to eat. This is the most basic, the simplest truth. We have to eat to stay alive. There is no way around this, no easier way to explain it. Things that live want to keep living. I grow food because I am attached to my life on this planet. We need to eat, and in order to do that, we kill a lot of things. We grow broccoli and corn and cucumbers, but we kill a lot of other plants, plants with names of their own: pigweed, purslane, ragweed, mustard root, dandelion, bindweed, sedge grass. We kill a lot of bugs – potato beetles, bean beetles, horn worms, aphids. Everything that eats must also kill. You can spray a field of potatoes with poison to kill all the potato beetles. Or you can spend hours in the hot sun moving down the row by hand, examining the leaves for beetles and squishing every one you see. This is a large part of our work in July: killing potato bug larva one by one, before they can perform the most basic act of survival and make more of themselves. In exchange for the life of a potato beetle we get a hard brown potato. A meal. I don’t know if this is a fair trade, but it is a trade I’m willing to make. I’m walking down those rows squishing those bugs by hand because the alternative is a lot of needless death.

There are complexities upon complexities in farming. I didn’t know how to answer that young girl’s question and I still don’t. All I have to offer her are the truths I know and refuse to ignore, the few hard facts that do not change, that shape our relationship to the land. Everything that eats must also kill. Everything that lives only wants to keep living, only wants to be remembered. We need to eat. We need to eat.

It is the end of September, and it is hoarding season. I am storing away onions and kabocha squash, and making of my kitchen an offering: applesauce, tomato sauce, thick garlic broth, raspberry jam, pumpkin butter, pickled beets, salsa. The nights are getting colder and my kitchen is gathering steam. It is not enough to fill our pantries with glass jars that remind us of our need for the land and what it will give us if we are patient and careful. It is not enough, but it is a start. My body knows what it needs. It is the season of yellow onions and butternut squash. I am filling my house with the scents of things that come from the earth: sweet basil and sharp garlic, roasted pumpkin, baked apples, honey. Winter is coming and this is the only thing I know how to do. I am filling my house with this good, solid food, this food that has the hard work of hands stitched into its flesh, this food that carries in its seeds both life and death, this food that is sustence and sunlight, that is patience and reverence, this food that binds us to the earth and blesses us and sustains us, this food that is our one undeniable prayer.

Wednesday, September 26, 2007

Rosh Hashanah Poem

I know Rosh Hashanah is over, but it's still the season...

Here’s to a sweet new year.

Here’s to the red and golden skins of apples.

Here’s to wind and other small things that sing.

Here’s to the names of fruits, names that are prayers, names you can hold in your mouth for a long, long time, names that change each morning when the new light pours over them, names that have no endings.

Here’s to a sweet new year.

Here’s to water.

Here’s to the thousand shades of brown that pass through every ordinary day.

Here’s to dirt.

Here’s to a sweet new year.

Here’s to yellow squash soup

and sweet onions cooked a long time in a coal-black skillet

and here’s to the years of pride and loneliness in that skillet’s dark, oily bowl,

here’s to the stories written there, the Sunday morning pancakes, the first chard of the season, the blossom of one egg yolk exploding into that expanse of space, meaning sustenance.

Here’s to a sweet new year.

Here’s to enough for dinner.

Here’s to the bottoms of feet that carry hearts.

Here’s to a sweet new year.

Here’s to honey that spills over from a glass jar, honey that opens love where it blooms, honey thick and warm and oatmeal-colored, honey that holds together families, honey that sings an answer to darkness with its slow spiral off a wooden spoon.

Here’s to rivers with fish in them that jump, and frogs that lay eggs, and the moment when everything hatches, everything opens, everything finally breaks new and trembling into the world, tumbles into daylight and stays.

Here’s to a sweet new year.

Here’s to the weight of a ceramic mug between your hands

and here’s to the steam that rises from hot black tea, that weaves itself into the fabric of the kitchen and disappears.

Here’s to what we’ve lost.

Here’s to a sweet new year.

Here’s to patched jeans and rain boots and wool hats and sweaters.

Here’s to soup in blue enamel pots and familiar faces gathered around tables and nut-brown loaves of round raisin challah.

Here’s to prayers older than bone

and firelight

and songs older than prayer.

Here’s to a sweet new year.

Here’s to the things that hold us up.

Here’s to the things that let us down.

Here’s to what we can’t let go.

Here’s to what opens us, and what closes us.

Here’s to what we can’t sing.

Here’s to the secret spaces in hearts where words don’t go.

Here’s to what we can touch with the roughened skin of our fingers.

Here’s to a sweet new year.

Here’s to stinging blue afternoons and mornings cloaked in snow.

Here’s to the days that have blessed us with their patience and their color.

Here’s to the blessings we’ve given each other and the blessings we’ve given the land,

and here’s to the laugher we’ve received and the darkness we’ve accepted,

and here’s to hunger and here’s to fulfillment.

Here’s to a sweet new year.

Here’s to the breath we’ve breathed.

Here’s to a sweet new year.

Here’s to the names of our grandmothers and here’s to their prayers, to their sweat, their thick woolen coats, their sadness, their socks.

Here’s to the places we’ll never go with them.

Here’s to what we remember about the lines in their faces and the creases in their laughter.

Here’s to bone.

Here’s to a sweet new year.

Here’s to bread and honey.

Here’s to blood.

Here’s to a sweet new year.

Here’s to some silence and some noise.

Here’s to some rain and some sweet blue days

and here’s to some bread that doesn’t rise

and some crops that fail

and here’s to a harvest to carry us through the winter

and to an emptiness that will sustain us there.

Here’s to wind that breaks boughs and sings us to sleep

and honors our loneliness.

Here’s to our muscles and our madnesses.

Here’s to some little deaths and some big deaths

and here’s to the moments that change us, and name us, and hold us,

some big ones and some little ones.

Here’s to a sweet new year.

Here’s to the red and golden skins of apples.

Here’s to wind and other small things that sing.

Here’s to the names of fruits, names that are prayers, names you can hold in your mouth for a long, long time, names that change each morning when the new light pours over them, names that have no endings.

Here’s to a sweet new year.

Here’s to water.

Here’s to the thousand shades of brown that pass through every ordinary day.

Here’s to dirt.

Here’s to a sweet new year.

Here’s to yellow squash soup

and sweet onions cooked a long time in a coal-black skillet

and here’s to the years of pride and loneliness in that skillet’s dark, oily bowl,

here’s to the stories written there, the Sunday morning pancakes, the first chard of the season, the blossom of one egg yolk exploding into that expanse of space, meaning sustenance.

Here’s to a sweet new year.

Here’s to enough for dinner.

Here’s to the bottoms of feet that carry hearts.

Here’s to a sweet new year.

Here’s to honey that spills over from a glass jar, honey that opens love where it blooms, honey thick and warm and oatmeal-colored, honey that holds together families, honey that sings an answer to darkness with its slow spiral off a wooden spoon.

Here’s to rivers with fish in them that jump, and frogs that lay eggs, and the moment when everything hatches, everything opens, everything finally breaks new and trembling into the world, tumbles into daylight and stays.

Here’s to a sweet new year.

Here’s to the weight of a ceramic mug between your hands

and here’s to the steam that rises from hot black tea, that weaves itself into the fabric of the kitchen and disappears.

Here’s to what we’ve lost.

Here’s to a sweet new year.

Here’s to patched jeans and rain boots and wool hats and sweaters.

Here’s to soup in blue enamel pots and familiar faces gathered around tables and nut-brown loaves of round raisin challah.

Here’s to prayers older than bone

and firelight

and songs older than prayer.

Here’s to a sweet new year.

Here’s to the things that hold us up.

Here’s to the things that let us down.

Here’s to what we can’t let go.

Here’s to what opens us, and what closes us.

Here’s to what we can’t sing.

Here’s to the secret spaces in hearts where words don’t go.

Here’s to what we can touch with the roughened skin of our fingers.

Here’s to a sweet new year.

Here’s to stinging blue afternoons and mornings cloaked in snow.

Here’s to the days that have blessed us with their patience and their color.

Here’s to the blessings we’ve given each other and the blessings we’ve given the land,

and here’s to the laugher we’ve received and the darkness we’ve accepted,

and here’s to hunger and here’s to fulfillment.

Here’s to a sweet new year.

Here’s to the breath we’ve breathed.

Here’s to a sweet new year.

Here’s to the names of our grandmothers and here’s to their prayers, to their sweat, their thick woolen coats, their sadness, their socks.

Here’s to the places we’ll never go with them.

Here’s to what we remember about the lines in their faces and the creases in their laughter.

Here’s to bone.

Here’s to a sweet new year.

Here’s to bread and honey.

Here’s to blood.

Here’s to a sweet new year.

Here’s to some silence and some noise.

Here’s to some rain and some sweet blue days

and here’s to some bread that doesn’t rise

and some crops that fail

and here’s to a harvest to carry us through the winter

and to an emptiness that will sustain us there.

Here’s to wind that breaks boughs and sings us to sleep

and honors our loneliness.

Here’s to our muscles and our madnesses.

Here’s to some little deaths and some big deaths

and here’s to the moments that change us, and name us, and hold us,

some big ones and some little ones.

Tuesday, September 25, 2007

Why I want to be a Farmer

1.

Because kale

when you dip it into a basin of cold water

and lift it out to shake dry,

sings,

scattering water like silver

into the quiet morning.

2.

Because I like the names of tomatoes:

Cherokee Purple. Black Prince.

Sungold.

Fox cherry. Brandy Rose. Orange Blossom.

3.

Sometimes

out in the fields at dawn

alone

the sun is rising in the east

the moon is setting in the west.

4.

If you listen closely,

onions will tell you how to weather storms

basil will teach you to write your name with scent

and pumpkins will whisper in your ear

the secret word for home.

5.

I want calluses

just below my thumbs

in the place where the hoe touches my skin.

6.

Once, harvesting beets,

a family of wild turkeys

watched me working as they walked across the meadow.

7.

Also the names of tools:

Hoe, harrow, rake, plough.

Spade, trowel, knife.

8.

Because of dirt and sky

and what grows

in the endless silence between them.

9.

And the names of herbs:

Tarragon, thyme, parsley, sage, cilantro.

Rosemary.

10.

If you could spend all day in a place full of rosemary,

wouldn’t you?

11.

It is as close as I have ever come to having a conversation with the earth.

12.

Because

on a cold blue afternoon

at the end of September

the sunlight on the piles of winter squash

curing in the field –

butternut, Hubbard, acorn, delicata –

is as much beauty

as I can ask for

in one lifetime.

Because kale

when you dip it into a basin of cold water

and lift it out to shake dry,

sings,

scattering water like silver

into the quiet morning.

2.

Because I like the names of tomatoes:

Cherokee Purple. Black Prince.

Sungold.

Fox cherry. Brandy Rose. Orange Blossom.

3.

Sometimes

out in the fields at dawn

alone

the sun is rising in the east

the moon is setting in the west.

4.

If you listen closely,

onions will tell you how to weather storms

basil will teach you to write your name with scent

and pumpkins will whisper in your ear

the secret word for home.

5.

I want calluses

just below my thumbs

in the place where the hoe touches my skin.

6.

Once, harvesting beets,

a family of wild turkeys

watched me working as they walked across the meadow.

7.

Also the names of tools:

Hoe, harrow, rake, plough.

Spade, trowel, knife.

8.

Because of dirt and sky

and what grows

in the endless silence between them.

9.

And the names of herbs:

Tarragon, thyme, parsley, sage, cilantro.

Rosemary.

10.

If you could spend all day in a place full of rosemary,

wouldn’t you?

11.

It is as close as I have ever come to having a conversation with the earth.

12.

Because

on a cold blue afternoon

at the end of September

the sunlight on the piles of winter squash

curing in the field –

butternut, Hubbard, acorn, delicata –

is as much beauty

as I can ask for

in one lifetime.

Monday, September 24, 2007

Some Things You Might Notice at a Farm in a Day

1. Your body moving. Especially your arms as they lift, your knees bending, the curve of your back as you move down the bed, weeding.

2. Light. On radishes in early morning, darkening the spinach in late afternoon. The way it saddens and deepens the evening as it softens. Shinning all over the pumpkins, making them glow rounder, fuller. How it dazzles when you walk into it. The way it makes dry leaves into glitter. On your hands as you pull tomatoes from the vine. How it changes the texture of the sky.

3. Eleven geese flying south in perfect formation. Their sleek backs against the blue sky, their wings moving in rhythm like small black waves. Their calls, which are like the sound a heart might make, flying away.

4. The unique color of one red onion as you clean a crate of them. Dark burgundy, plum-metallic, gleaming.

5. The scent of garlic on your hands.

6. Sudden wind that shakes the trees and rips through the tall rows of amaranth and sunflowers, bringing with it the scent of evening: sharp and musky, like sweet hay and freshly-tilled soil.

7. The sun on your back.

8. Green kale that turns to silver in cold water. Yellow tomatoes. White turnips. Purple beets, their greens veined with red. Sweet peppers marbled yellow and green, like grass in early May. The miracle that all these things come from the earth.

9. Thirst.

2. Light. On radishes in early morning, darkening the spinach in late afternoon. The way it saddens and deepens the evening as it softens. Shinning all over the pumpkins, making them glow rounder, fuller. How it dazzles when you walk into it. The way it makes dry leaves into glitter. On your hands as you pull tomatoes from the vine. How it changes the texture of the sky.

3. Eleven geese flying south in perfect formation. Their sleek backs against the blue sky, their wings moving in rhythm like small black waves. Their calls, which are like the sound a heart might make, flying away.

4. The unique color of one red onion as you clean a crate of them. Dark burgundy, plum-metallic, gleaming.

5. The scent of garlic on your hands.

6. Sudden wind that shakes the trees and rips through the tall rows of amaranth and sunflowers, bringing with it the scent of evening: sharp and musky, like sweet hay and freshly-tilled soil.

7. The sun on your back.

8. Green kale that turns to silver in cold water. Yellow tomatoes. White turnips. Purple beets, their greens veined with red. Sweet peppers marbled yellow and green, like grass in early May. The miracle that all these things come from the earth.

9. Thirst.

Three Meals

Breakfast:

Pumpkin bread with thick honey, black tea. The sun is rising behind the oak tree in the back yard. Quiet.

Lunch:

Leftover tomato pie at the picnic table in the shade of the maple tree. Laughing with farmers under the blue sky on the edge of the field of flowers. Amaranth, Mexican sunflower, ageratum, marigold, celosia. Onions cooked a long, long time. Tomatoes simmered down to a thick red pulp with fresh basil, salt and pepper, parsley, garlic. Parmesan and mozzarella. Baked golden and steaming in a pie crust made with butter, flour, water and salt. A small breeze and the sun through the leaves. The table dappled now with sunlight, now with shadow. Empire apples and honey. Cold water.

Dinner:

Frittata with lots of good stuff: onions, garlic, red and yellow peppers, chard, sweet corn, basil. Roasted red and white potatoes with garlic, olive oil and a pinch of tarragon. The raw red potatoes blush pink and darken to purple when they’re cooked. The kitchen smells like basil and corn. We open a bottle of Spanish red. We make the first fall salad of the year: dark leaves of spinach, harvested an hour earlier, sliced apples, New York cheddar cheese, toasted pecans. The sun gets lower and lower in the sky. It’s gone when I pull the frittata out of the oven. We sit at the table and eat and talk. The two most basic things. For dessert: apple pie and homemade cinnamon ice cream. Ginger tea. The pie is warm and full of apples and tastes like fall melting in your mouth.

This is as much as I can fill myself with every day. This is as much as I can take from the world. This is what I want to give away: the feeling that spreads through your body as you take a bite of hot apple pie or earthen green spinach and sharp cheese. It starts on your tongue and flows down your throat and into your gut and winds around your heart and enters your bloodstream. I don’t know all the answers, but I know that a day full of pumpkin bread and apples and roasted potatoes is the first half of a prayer. Something happens to us when we eat good food. Something opens up in us, something softens. I don’t have all the answers, but I am going to start with this: fall is brewing in the hard skies and the dark mornings. My house will be full of gingerbread and leeks, thick potato soup and apple-cheddar omelets, pumpkin pies and maple cookies and long-cooked onions, always. My house will be full of sustenance and my doors will be open.

May wonder and gratitude bless all our bread.

Pumpkin bread with thick honey, black tea. The sun is rising behind the oak tree in the back yard. Quiet.

Lunch:

Leftover tomato pie at the picnic table in the shade of the maple tree. Laughing with farmers under the blue sky on the edge of the field of flowers. Amaranth, Mexican sunflower, ageratum, marigold, celosia. Onions cooked a long, long time. Tomatoes simmered down to a thick red pulp with fresh basil, salt and pepper, parsley, garlic. Parmesan and mozzarella. Baked golden and steaming in a pie crust made with butter, flour, water and salt. A small breeze and the sun through the leaves. The table dappled now with sunlight, now with shadow. Empire apples and honey. Cold water.

Dinner:

Frittata with lots of good stuff: onions, garlic, red and yellow peppers, chard, sweet corn, basil. Roasted red and white potatoes with garlic, olive oil and a pinch of tarragon. The raw red potatoes blush pink and darken to purple when they’re cooked. The kitchen smells like basil and corn. We open a bottle of Spanish red. We make the first fall salad of the year: dark leaves of spinach, harvested an hour earlier, sliced apples, New York cheddar cheese, toasted pecans. The sun gets lower and lower in the sky. It’s gone when I pull the frittata out of the oven. We sit at the table and eat and talk. The two most basic things. For dessert: apple pie and homemade cinnamon ice cream. Ginger tea. The pie is warm and full of apples and tastes like fall melting in your mouth.

This is as much as I can fill myself with every day. This is as much as I can take from the world. This is what I want to give away: the feeling that spreads through your body as you take a bite of hot apple pie or earthen green spinach and sharp cheese. It starts on your tongue and flows down your throat and into your gut and winds around your heart and enters your bloodstream. I don’t know all the answers, but I know that a day full of pumpkin bread and apples and roasted potatoes is the first half of a prayer. Something happens to us when we eat good food. Something opens up in us, something softens. I don’t have all the answers, but I am going to start with this: fall is brewing in the hard skies and the dark mornings. My house will be full of gingerbread and leeks, thick potato soup and apple-cheddar omelets, pumpkin pies and maple cookies and long-cooked onions, always. My house will be full of sustenance and my doors will be open.

May wonder and gratitude bless all our bread.

Sunday, September 23, 2007

Yom Kippur

I know this is a little outdated, since Yom Kippur was yesterday and I wrote this a few days before, but it seems relevant...

It has been so cold in the mornings I have been wearing two pairs of socks inside my boots and a hat. The boots change everything about the day. The ground feels different through a half inch of leather. It is dark when I wake up in the mornings now. I wake up in darkness. Last night I made apple pie. Butter, flour, water, salt. Apples, cinnamon, ginger, nutmeg, honey. We ate it this morning standing around the harvest board, our hands wrapped around mugs of coffee, our breath white against the sky. The sky has been too bright for me recently, and the moon has been too sharp.

Yom Kippur is Saturday. I am going to spend the whole day cooking. I am going to make applesauce in a blue enamel pot and oatmeal bread that fills the whole kitchen with its nutty scent, and pumpkin pie that glows. We harvested pumpkins yesterday. Afterwards I felt strong. It is a good afternoon’s work, harvesting a truckload of pumpkins. I like my body when I’m working. In the field I feel young and beautiful. I can feel the ribs of my muscles and the outline of my heart as it beats inside my chest. The pumpkins shone orange and gold in the afternoon sunlight, and standing in the back of the dump truck as the crew tossed me pumpkin after pumpkin, and the stack behind me grew taller and fatter and brighter, I thought: I could die from the vastness of this. The field is sacred and so is work and when I can feel my muscles moving in their cages I know I am saying a true prayer.

It is Yom Kippur on Saturday and I am going to make pie with the pumpkins I harvested while the sun sank lower in the sky and my skin gleamed with happiness and sweat. They are lined up now on my kitchen table. They speak of bounty and autumn and they light up the kitchen. I am going to make tomato sauce with only the bare essentials: tomatoes, basil, garlic, olive oil, salt. I am going to fill the house with the scents of cinnamon and cloves and rising bread and onions sizzling golden in the dark bottom of the skillet. I am going to get up early and spend the day in the kitchen, the prayer-center of the house, the temple of everything I hold sacred. I don’t feel like a Jew today and I don’t want to atone. There’s enough atonement in the world already. I only want to celebrate. I only want to eat and be grateful.